How It’s Done

Evidence That May be Collected

Hair - Analysts can tell investigators if individual hairs are human or animal, and in the case of human hair, where on the body the sample originated. Samples can be tested to determine the color, shape and chemical composition of the hair, and often the race of the source individual. The presence of toxins, dyes and hair treatments are noted. This information can assist investigators in including or excluding particular individuals as the source of the hair. If the hair still has a follicle (root) attached, DNA testing may be used to identify an individual; otherwise, hair comparison is typically used only to exclude.

Collection: Collected samples are sent to the laboratory along with control samples from a suspected individual. Control samples should include hair from all parts of the head and, for pubic hair, the area should be combed for foreign hairs prior to sample collection. Hair samples are primarily collected using tweezers.

Fiber - Fibers are threadlike elements from fabric or other materials such as carpet. Most are easily identifiable under a microscope. Fibers fall into three classifications: natural (animal or plant fibers like wool, cotton or silk), synthetic (completely manmade products including polyester and nylon) and manufactured (containing natural materials that are reorganized to create fibers such as rayon).

Fibers are useful in crime scene investigation because their origins can be identified. A carpet fiber on a person’s shoe can indicate the individual’s presence at a crime scene. However, fibers are very mobile and can become airborne, get brushed off or fall from clothing. This mobility makes timely collection crucial to prevent loss of material or cross-contamination.

Collection: Fibers cling to other fibers and hair, but may be easily brushed off. When approaching a scene, investigators will attempt to pinpoint the most probable locations for deposited fibers. For example, the carpeting under and surrounding a victim’s body, clothing from the victim or a suspected weapon are likely places to find fibers.

Common collection methods include individual fiber collection using tweezers or vacuuming an area and sorting the materials at the laboratory. Trace evidence can also be gathered by tape lifting, however, this is not ideal due to the destructive nature of adhesives.

Samples that potentially contain fibers should be separately bagged to prevent cross-contamination.

References to collection and storage of fiber and hair evidence can be found in the Quality Documents Program, Laboratory Physical Evidence Bulletin #4.

Glass - Glass can be used to gather evidence, for example collecting fingerprints or blood from a broken window; however, glass also has a place in the trace evidence section. Broken glass fragments can be very small and lodge in shoes, clothing, hair or skin. Gathering glass fragments from a crime scene can be valuable in determining end-use or connecting people and objects to places. For example, windshields have a different color and composition than a drinking glass or a lead crystal vase, so glass fragments on an individual’s clothing could be compared to those collected at a hit-and-run scene to determine if that individual was present.

Windshield fracture pattern. (Courtesy of NFSTC)

Collection: Trace examiners may use magnification and light to find glass fragments on clothing, an individual or at a crime scene and extract those using tweezers. Tape may also be used to collect glass samples, but the residue left from the adhesive makes this a less desirable collection method.

References to collection and storage of glass can be found in the Quality Documents Program, Laboratory Physical Evidence Bulletin #3.

Paint - Painted surfaces are everywhere and the wide variety of layered colors, lusters and types often make paint high-value as evidence. For example, paint transferred when one vehicle hits another vehicle, a pedestrian or a building can be matched to potentially identify the car in question. In a property crime where a tool is used to break into a building, paint transferred to or from the tool can connect the tool to the location. Analyzing automotive paint can identify the make, model and sometimes the year of a vehicle.

Collection: To collect paint, investigators document the scene, then peel off, or excise, small amounts of paint from the source, being careful to gather all layers. Samples as small as one square millimeter can be used for testing. For a car crash scene, paint samples from the point of contact would be photographed, collected and stored in such a way as to protect the edges for further examination. This is particularly important when examining for fracture matches.

Paint samples are typically collected by scraping small sections down to the metal or original surface or using tweezers to collect chips already dislodged.

References to collection and storage of paint can be found in the Quality Documents Program, Laboratory Physical Evidence Bulletin #2.

Who Conducts the Analysis

Most large laboratories or laboratory systems have a trace evidence section. Analysts have a variety of backgrounds, but most require a degree in a natural science with additional certification or additional study in chemistry, particularly if the primary degree is not in chemistry. Certification is generally conferred on an individual who has achieved specific education, training, experience and performance on competency tests as designated by the certifying organization. Some areas of trace evidence have individual certification programs, which are facilitated by professional associations and boards. The American Board of Criminalists certifies trace examiners using a General Knowledge Exam (GKE) and specialty exams in fibers, hair and glass.

How and Where the Analysis Is Performed

Since trace evidence covers a wide variety of subcategories, there is similar variety in the testing that is performed. Specialized testing may be done outside of the local laboratory at regional or national facilities. The type of test performed and the range of information provided vary by the type of evidence tested. For example, analysis of a strand of hair may yield information on the race and general health of the donor, while analysis of a paint sample would likely yield the manufacturer of the paint and its commercial use.

Hair: Hair samples are tested primarily by microscopic comparison and chemical analysis. Microscopic comparison identifies the shape, color, texture and other visual aspects of the sample, while chemical analysis indicates the presence of toxins, drugs, dyes and other chemicals. In some cases hair is subjected to DNA analysis. Learn more about DNA ▸

Fibers: Trace evidence analysts often have only mere strands to work with. From these strands, fiber testing is done using high-powered comparison microscopes to compare texture and wear in a side-by-side assessment. Chemical analysis can determine the chemical composition of the fibers. In the case of synthetic fabric or carpet, this information can be used to trace the product to the manufacturer using standards databases, further enhancing the probative value of the evidence.

Glass: Glass can yield valuable information through fracture marks, lines and patterns. Testing for unique characteristics such as color, optical properties and density can determine the type of glass, for example a window pane, vase or glass bottle. A detailed elemental analysis, including specific impurities, can be done using laser ablation mass spectrometry, induction-coupled mass spectrometry, X-ray fluorescence or other instruments.

Glass shards can be used for sourcing the glass and also to collect potential biological evidence. (Courtesy of NFSTC)

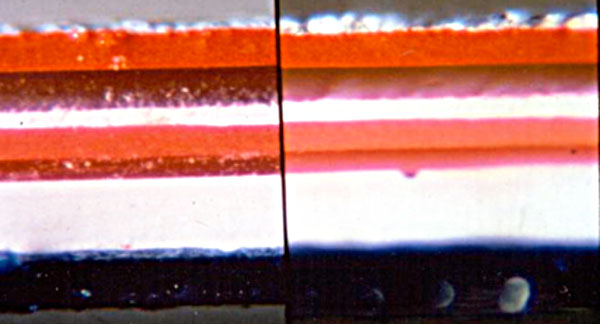

Paint: Powerful comparison microscopes are used to compare colors, thickness and layer patterns, and luster or to match fragments and tears. Chemical testing, such as Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography (PYGC) can be used to determine chemical composition, colors and pigments and other qualities.

Microscopic comparison of paint samples can show layers of paint, primer, coatings, scratches and other damage that can uniquely match two pieces or otherwise provide class identification information. (Courtesy of NFSTC)